A lobby full of masterpieces

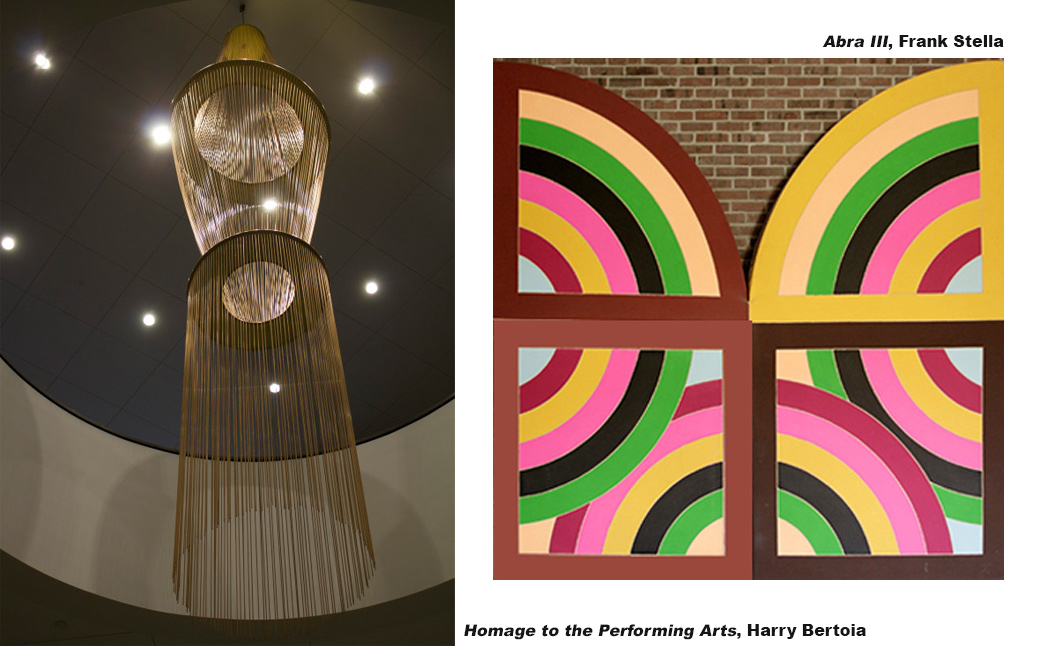

“I build sculptures that can move in the wind, or that can be touched and played, like an instrument,” Bertoia said in an NPR interview a few years before his death in 1978. A pioneering sound artist, Bertoia made recordings as he touched various sculptures together in his barn. The recordings were released as Sonambient albums. Unfortunately, we don’t know if Bertoia ever tried playing Homage to the Performing Arts. This sculpture was entirely conserved to its original splendor in 2015 and returned as the centerpiece of the lobby.

Seymour Lipton’s bronze sculpture The Voyager (1964) is another highlight of the Annenberg Center lobby. Also installed in 1971, it was donated by Mrs. Zellerbach and her children. Lipton (1903-1986) was an Abstract Expressionist sculptor and a member of the New York School. Originally trained as a dentist, Lipton turned his focus to sculpture in 1932, working in wood, metal and bronze. Many of his works focus on the themes of nature, flight and war. The Voyager is a fine example of his non-objective sculpture.

Near the Walnut Street entrance of the Annenberg Center’s lobby hangs the painting Opposition (1972) by Michael Krausz (b.1942). A Swiss-born American philosopher, Krausz was a philosophy professor at Bryn Mawr College for 45 years and founding music director and conductor of the Great Hall Chamber Orchestra. A self-taught artist, Krausz studied at the Philadelphia College of Art in 1970s. Opposition is composed of eight red, shaped canvases. The joined pieces form a distinctive positive shape whose outline highlights the negative—or empty—space of the wall. “My art integrates my philosophical and musical concerns as well,” the multitalented artist noted.

In the 1960s, Frank Stella (b. 1936) gained renown for creating abstract paintings that have no pictorial illusions, or psychological or metaphysical references. His flat surfaces and bold colors are known as hard-edge painting, and were in sharp contrast to paintings by the Abstract Expressionists. Abra III (1968) is a superb example of Stella’s Protractor series with its bold, acrylic colors and motifs of arcs, half-circles and horizontal and vertical lines that intersect at right angles. The painting is named after the circular city Stella had visited while traveling in the Middle East. Through the device of the protractor, the use of acrylic and fluorescent pigments, and shaped canvas, Stella’s paintings forged a new style of American abstraction.

Lynn Marsden-Atlass is the Executive Director of the Arthur Ross Gallery and University Curator. Learn more about Penn’s art collection or engage with the Arthur Ross Gallery and its COVID-19 Citizen Challenge, a crowd-sourced exhibition encouraging you to select artwork and share what it means to you.